Basic Research

My research topics cover everything that has to do with automated reasoning, including its connections with theoretical computer science and philosophy. In particular, it is possible to identify three forms of logical reasoning, typically known as deduction, abduction and induction, which, together, allow to achieve interesting behaviours.

To better understand my research it is necessary to first introduce some basic concepts. The above forms of logical reasoning, in particular, rely on a set of rules, each consisting of a premise, a material condition and a conclusion, which represent the knowledge the system has about how the world works. Such rules constitutes what, in knowledge representation, is typically referred to as TBox. In order to represent the world and, therefore, allow a machine to think about it, furthermore, in addition to the rules there is the need of a set of assertions which, depending on the reasoning needs, can be translated into facts and goals. Such assertions constitutes what, in knowledge representation, is typically referred to as ABox.

Deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning determines whether the truth of a conclusion can be determined based solely on the truth of the premises. Given a set of facts, in particular, deductive reasoning tries to apply the rules, from premises to conclusions, to deduce new information.

A typical example of deductive reasoning is the one adopted in the most classic of Aristotelian syllogisms. The rule, in this case, expresses the concept that “all men are mortal”. From a formal point of view, we can express this rule as $\forall x . man \left( x \right) \Rightarrow mortal \left( x \right)$. By being aware that Socrates is a man, we can add the $man \left( Socrates \right)$ fact to the knowledge base. Through deductive reasoning, at this point, a reasoning engine could deduce the $mortal \left( Socrates \right)$ fact, which indicates that Socrates is mortal. Note that the newly inferred fact is, in turn, a fact and, therefore, could trigger further deductive reasoning.

The sequential application of deductive reasoning is typically referred to as forward chaining, and is adopted in numerous software architectures such as knowledge based systems, rule based systems, expert systems, production systems, etc. The technical challenges, in this form of reasoning, are linked to:

- Match: the verification of the premises of the rules. As the number of rules increases, indeed, verifying all the rules at each update quickly becomes inefficient. For this reason algorithms such as the RETE algorithm are adopted.

- Conflict-Resolution: In the event that the premises of several rules are verified at the same time, it is necessary to establish which rule to apply and, consequently, which facts to deduce. Typically, the approach is taken of choosing the rule whose verified premise is considered the most constrained.

- Rule definition: As the complexity of the modeled system increases, the definition of rules becomes a pain. In fact, the need for two professional figures soon emerges: the domain expert, who knows how the system to be modeled works in the real world, and the knowledge engineer, who knows how the inference engine works.

The need to have two professional figures, with different skills, who must cooperate for the construction of a deductive system, makes adopting these forms of reasoning based on rules less and less attractive. Nonetheless, some interesting properties of these systems remain valid. Deductive systems based on formal rules, in particular, have a predictable behavior and, thanks to the presence of the rules, they are easily explainable. It is also an excellent tool for creating interactive systems.

Abductive reasoning

Abductive reasoning, sometimes called inference to the best explanation, selects a cogent set of preconditions. Given a true conclusion and a rule, it attempts to select some possible premises that, if true also, can support the conclusion, though not uniquely. This form of reasoning allows us to infer the premises of the rules starting from their conclusions.

To explain this form of reasoning we can, once again, refer to the previous Aristotelian syllogism introduced. The $\forall x . man \left( x \right) \Rightarrow mortal \left( x \right)$ rule, stating that all men are mortal, in particular, remains the same. What changes are the initial assertions. In the case of abduction, in particular, instead of knowing that Socrates is a man, we know that Socrates is mortal. The $mortal \left( Socrates \right)$ assertion becomes a goal to be achieved. And it can be achieved by applying the rule backwards, from the consequences to the premises, abducing $man \left( Socrates \right)$ from it.

As in the deductive case, the abduction can be iterated, making the inferred assertions additional (sub) goals to be achieved. This form of reasoning is typically called backward chaining, and is adopted by several software architectures such as knowledge based systems, rule based systems, expert systems, logic programming, etc. This form of reasoning lends itself very well to achieving goal-oriented behaviors and, therefore, can be used to make planners. An example of such planners is oRatio which, as described in [1], extends abductive reasoning with forms of constraint-based reasoning that allow to represent numerical information and to schedule the planned activities over time.

Inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning attempts to generate, e.g., from a set of examples, the rules which allow the previous forms of reasoning. After numerous examples are taken to be a conclusion that follows from a precondition, a rule is hypothesized.

Putting things together

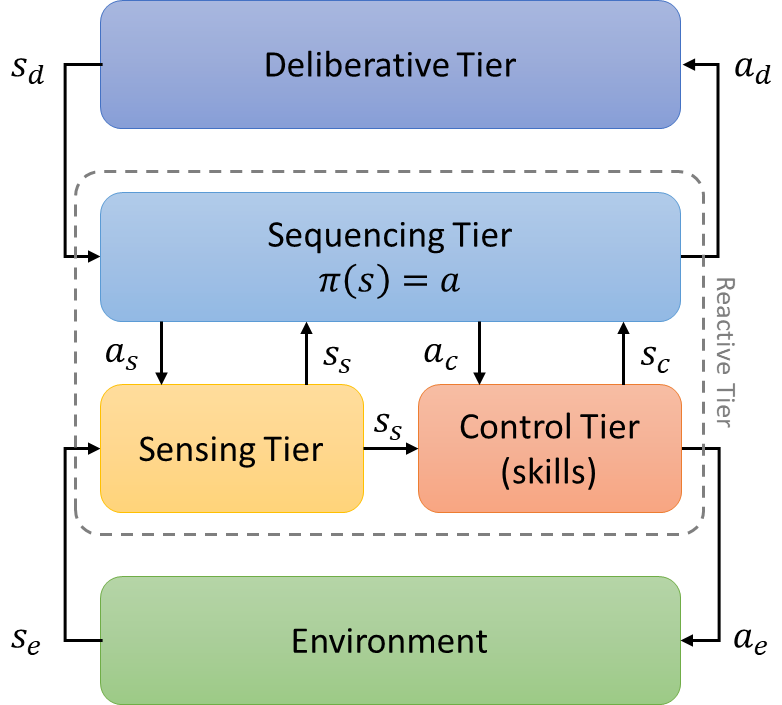

Each of the foregoing forms of reasoning has its strengths and weaknesses, both technical and intrinsic. A theme that I have always considered interesting concerns the development of architectures capable of orchestrating these different forms of reasoning, so as to exploit their strengths in a homogeneous way. An architecture that is proving to be quite flexible is shown in the following figure.

This architecture is inspired by the classic three-tier architectures typically used in robotics. Thanks to its flexibility, however, it allows to solve real problems and, at the same time, to respond to some research needs. Specifically, the architecture consists of a deliberative tier responsible, through abductive reasoning, for the generation, the execution and the dynamic adaptation of the plans; a sequencing tier which, through the application of a policy, performing deductive reasoning, executes a sequence of actions according to the current state of the system; and a sensing and a controlling tier, which respectively interprets data produced by sensors and translates the sequencer’s actions into lower level commands for the actuators.

Particularly interesting from an execution perspective, it is worth noting that the state, according to which actions are selected from the sequencer tier policy, is described by the combination of three distinct states:

- the $s_s$ state, generated by the sensing tier and characterized as a consequence of the interpretation of sensory data, is able to represent, for example, the intentions of the users, the estimation of their current pose, the users’ emotions perceived from the camera, as well as situations which might be dangerous for both the users and for the robot;

- the $s_c$ state, generated by the control tier, representing the state of the controllers such as whether the robot is navigating or not, or whether the robot is talking to or listening to the user;

- the $s_d$ state, generated by the deliberative tier, representing the high-level commands generated as a result of the execution of the planned plans

Similarly, the actions executed by the sequencer tier can be of three distinct types:

- the $a_s$ actions, towards the sensors, responsible, for example, for their activation or for their shutdown;

- the $a_c$ actions, towards the controllers, responsible, for example, for activating contextual navigation commands as well as conversational interactions with the users;

- the $a_d$ actions, towards the deliberative tier, responsible, for example, for the creation and for the adaptation of the generated plans.

It is worth noting that, through the application of the $\pi\left(s\right)$ policy, the sequencing tier can act both indirectly on the environment, through the $a_c$ actions, and, through the $a_d$ actions, introspectively on other higher-level forms of reasoning adopted by the agent itself. The high-level actions generated by the deliberative tier while executing the plans, moreover, constitute only one component among those that determines the choice of the actions by the policy. Somehow, they are are not mandatory for the autonomy of the robot and represent a sort of “suggestions”, for the agent, on the things to do.

References

[1] De Benedictis, R. & Cesta, A. (2020). Lifted Heuristics for Timeline-based Planning. ECAI 2020. IOS Press. 2330-2337 (pdf).